How Do We Know That Franklin's Black?

Content warning: there’s an attempt at nuance here talking about racial stereotypes

Hey, There,

So, take a look at that image there. Charlie Brown and Franklin, right? There’s nothing more familiar in the world of comics than a couple of Peanuts characters. The strip’s protagonist and a member of the extended cast who’s Black, both drawn in Charles Schulz’s immediately-recognizable minimalist style.

But now try to disengage the part of your brain that immediately recognizes the two and just look at them as drawings. They’re both very simple, not very anatomical drawings of boys with round heads. Really, they’re black lines in white space denoting some shapes that we project meaning onto. We “know” that the one on the right is white and the one on the left is Black. How do we know this?

As someone who both makes and studies comics, this is a thing I’m fascinated with. Comics have a visual grammar, a whole system of images that our brains process to get information in shorthand in ways that our conscious brains don’t even really register (and, as the first of many clarifying asides, these systems are extremely culturally specific, so that Japanese comics have a somewhat different visual grammar system from American comics; or even American comics from 1920 have a very different visual grammar system from American comics in 2020). There are lots of sub-branches of this visual grammar, including ways to communicate action, and the passage of time, and emotions, and speech, and so on. But I want to focus in on one area of this that’s really important, really fraught, and really underexamined: the way comics use little visual elements to communicate race or ethnicity. I think this is fascinating stuff; it can also be uncomfortable stuff, so I guess be ready.

Scott McCloud’s book Understanding Comics is kind of the cornerstone of modern comics theory. It’s not encyclopedic or even universally right, but it’s full of really good starting points for discussions. One of the things McCloud suggests, when talking about why people are drawn to comics, is what he calls his mask theory. It essentially says that people like comics because simple, abstract drawings let us impose our own specifics onto them. So a photograph of Frank Sinatra is clearly Frank Sinatra, and you don’t really identify with it (unless you’re a really swingin’ cat); but a simple drawing of a circle with two dots and a line in it is kind of a generic everyface that’s a lot easier to identify with. And Charlie Brown is pretty close to that generic everyface.

McCloud never addresses this, but I think there’s an uncomfortable component to this: in a white supremacist culture (and god knows the boundaries of that are hotly debated, but in this context I’m using that to mean “a culture where whiteness is presumed to be the default, with all other populations defined by their difference from whiteness”), the unconscious pressure, especially for white readers, is to impose whiteness on generic cartoon drawings. I mean, think about Charlie Brown. Even without reading Peanuts, most (white) people would see this drawing and think “that’s a white kid.”* I want to be really super clear: I think that this is the way it works in our culture, but I’m trying to be descriptive without being approving.

*I can actually remember the first time I encountered this: I remember sitting around as an undergrad watching some anime that just happened to be on, and starting to wonder with increasing intensity why the hell Japanese animators had drawn all of the characters in this to be white. It took me over a decade to realize that they hadn’t, and that I had been the one projecting whiteness onto them.

If, in a white-dominated society, the default interpretation is that a generic cartoon drawing is white, a cartoonist wanting to show characters who aren’t white needs to differentiate them with some visual elements. Functionally, these visual elements are usually lines that indicate some kind of facial or physical feature. And here we really get into the weeds, because these visual signifiers often have a very uncomfortable overlap with lazy, often-offensive stereotypes; after all, they mostly work by indicating some element that “everybody knows” is associated with a minority group. And god knows that it’s all too common for cartoonists to exaggerate or center these fairly-stereotypical elements and move, intentionally or not, into out and out racial caricature.

But enough of this theory; let’s look at some specifics. For starters, let’s hop back to Charlie Brown and Franklin. As I said before, they’re essentially the same drawing,* with the difference that Charlie Brown has his weird indeterminate squiggle hair while Franklin has tightly curly hair on top of his head (in his first appearances, Franklin also had hatching, or a series of lines, drawn into his face to indicate a darker skin tone, but Schulz moved away from this pretty quickly, probably because the additional lines made Franklin’s facial features and expressions tougher to read; and of course in color strips, Schulz could rely on brown skin tones for Franklin).

*Schulz’s inclusion of Franklin into Peanuts wasn’t entirely successful, as I’ve written about at length elsewhere, but it was extremely well-intentioned, and I’ve always thought that it was kind of touching that Franklin was just Charlie Brown with a different haircut. The rest of the Peanuts cast had markedly differently-shaped heads, but Schulz really wanted to drive home the idea that Franklin was the same as the strip’s protagonist, not some mysterious Other. “I don’t see color” winds up being a very problematic stance for white people to take, and god knows Schulz dropped the ball with Franklin over the long haul, but his statement of sameness, looked at in the context of 1968, was at least a well-meaning one.

Garry Trudeau integrated the cast of Doonesbury not long after Schulz introduced Franklin into Peanuts. To my modern eye, his visual signifiers of the ethnicity of the first Black character, Calvin, come across as uncomfortable.

Doonesbury, March 11, 1971

Like Franklin, Calvin is drawn with curly black hair and hatching to indicate his darker skin tone; but Trudeau doesn’t extend the hatching to Calvin’s exaggerated lips, emphasizing them in a way that feels like it crosses a line into caricature (as with Franklin, the hatching lines also make it tough to read Calvin’s facial expression; indeed, this might be why Trudeau stopped hatching near his mouth).

Black Doonesbury characters, 1970s-2000s

Trudeau stuck with that same basic approach to signifying Blackness through the 70s, but seemed to change his approach as time moved on. As seen in the collage above, in the lower left the character Ray in the 1990s is indicated as Black purely by his hair and lips, without any hatching at all. Similarly, in the lower right, Elias in the 2000s is indicated as a person of color only by grayscale dots, with no facial feature signifiers used (in fact, I read Doonesbury online at that point, in a format that didn’t include all the gray tones, and didn’t realize from those images that Elias was even supposed to be Black).

Panel from Love and Rockets

Jaime Hernandez’s endlessly-praised-by-me Love and Rockets comics are extremely diverse, with an interesting signifier game going on. Hernandez, who is Mexican-American, is minimal with his ethnic signifiers. His style is “realistic” enough to allow a lot to be conveyed through characters’ clothing and hairstyles, and these elements do most of the work for his Latinx and white characters. Like Trudeau, though, Hernandez uses larger lips—as well as a broad nose--as an indicator of blackness for the character Danita and her son, as seen in the panel above (which may be the greatest panel in the history of comics).

So to hit pause here: as a white guy who tries not to be a terrible one, I am extremely not comfortable repeatedly typing “X non-Black cartoonist uses larger lips and/or broad noses to indicate that a character is Black.” It feels racist just to describe it. But the fact remains: this is how these cartoonists, none of whom I think of as particularly racist, indicate Blackness; whatever my discomfort, this is what they thought would be the most useful approach when they looked into the cartooning toolbox.

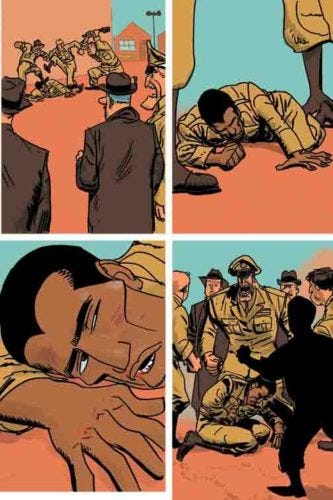

Moreover, I can think of at least one prominent Black cartoonist using the same tools. Kyle Baker, when working for Marvel on a provocative series about the Captain America serum being tried out first on Black soldiers, Tuskegee Experiment-style, uses a similar combination of hairstyle, broadened nose, and large lips to communicate Blackness*

Cover and panels from The Truth: Red, White, and Black

*the finished comic art shown here is in color, which also does a lot of work conveying ethnicity; but Baker’s initial drawing would have been in black and white.

Kyle Baker is certainly not a cartoonist to just go with the flow and use aesthetics he’s not comfortable with just to get along. If he’s using these visual indicators to convey Blackness, it’s because he thinks its effective and he’s OK with it.

Another Black cartoonist, Aaron McGruder, pointedly doesn’t use facial features as ethnic signifiers in his work. In The Boondocks (where, uniquely among the works I’ve talked about, the cast is default Black), hairstyles and clothes do all of the signifying work, with help from grayscale complexion tone.

To be honest, I’m not sure where this leaves us. I don’t think it’s enough for me to land on “well, one prominent Black cartoonist uses somewhat-stereotypical facial features as signifiers to indicate Blackness, so it’s universally ok!” I think it’s more like, it’s maybe OK, or at least the least bad option, but for god’s sake white cartoonists need to be extremely careful. The line between cartooning trope and out-and-out stereotype seems to be one that would be all too easy to swoop past, blithely unaware. I’d initially planned to include examples in this newsletter of white cartoonists getting it horribly wrong, just cannonballing right on past that line; but I decided that we’ve all seen it, and nobody needs a bunch of over-the-line racist comics in their newsletter.

I guess there’s one thing I’m sure, of, though: however uncomfortable it can get to figure out exactly how to represent Blackness in comics, it’s something that white cartoonists, including me when I’m in my cartooning mode, need to keep trying to figure out. Representation matters.

Right on. Be safe.

RECOMMENDATIONS

It’s probably gauche to recommend my own work. But what the hell, I’m feeling gauche this week.

First off: most mornings I get up, take a look at the Iowa City Police Log Twitter feed, pick one, and draw a one-panel comic illustrating it (my comics are also available on Instagram if you don’t like Twitter). As a friend pointed out, you read these and realize just how minor and not-needing-military-grade-armament most police calls are.

And more gaucheness: I just released an EP of myself covering Clash songs country-style. It’s called PSA With Guitar, and I’m super proud of it. I’d planned on working on a noise-rock album this year, but as things unfolded it just felt more and more like we were living in Strummer Times.

cover art by Rebecca Collins

SOME LINKS

Patrick Wyman is a historian and thinker whose work I’ve really come to appreciate lately. His newsletter is excellent in general, but this specific issue where he looks at what’s happening in Portland through the lens of a colonial apparatus turned on the home country is really amazing stuff.

CLOSING STUFF

OK, so here at the bottom, sorry for the ragged copy editing; my deal with myself was to keep this fast and loose, which is gonna mean typos. On the other hand, that also means it’ll actually come out, instead of being obsessed over.

If you have any thoughts/reactions/what have you about this, I’d love to hear about it, either by email or on Twitter. And if you know anybody who might dig this, please forward it on to them, or send ‘em the signup link! And thanks!