Churchill: A Portrait of an Old Heap

Don't look to Sutherland's painting for hagiography, or at the newsletter either.

Hey, There,

How’re you holding up in the pandemic zone? What’re your coping strategies?

Like a lot of people, we’ve fallen back on bingeing TV (pro tip: HBO’s adaptation of The Plot Against America is very good, but is not exactly what you’d call diverting comfort viewing). Right now, the main focus of our binge has been finally getting around to watching The Crown.

And you know what? It’s pretty good. I hadn’t expected this, but the show even dodges into art history-adjacent topics pretty often. Which makes sense, of course; conventional, traditional art history is absolutely dominated by the concerns of the rich and status-seeking*, and the Windsors are very much both. In particular, the first season episode “Assassins” actually works so well as a short standalone movie about an artist and his subject that I honestly think it could be approached that way. It definitely highlights one of the most fascinating problems in 20th century art, the shifting role of painted portraiture.

*This reminds me of when I was leaving the Minnesota Historical Society in 2002, during a budget-crisis-inspired mass staff exodus, to go work at the Minneapolis Institute of Art, and an obnoxious coworker who was kind of my office nemesis said, “have fun helping rich people play with their money over there” as kind of a parting curse.

Here’s the premise of the episode, which I guess I’ll have to spoil a little: it’s 1954, and Winston Churchill, deep into his second stint as Prime Minister, is about to turn 80. As a present for him, Parliament collectively pitches in to commission a portrait of him from the noted British painter Graham Sutherland. Churchill is wary, since Sutherland’s known as a modernist, but the two feel like they reach some level of mutual understanding by both talking about art and even recreating each other’s work.* Then Sutherland delivers the final portrait, which is both heavily stylized and not remotely flattering. Churchill’s wounded and outraged, and the two men argue over what the point of portraiture is to begin with. Churchill reluctantly accepts the painting, insulting it in public; and then his wife burns it back at his estate (and this really happened! Or at least his wife had it burned by servants).

*Churchill really was an amateur painter, albeit not that great of one, and one of the fun things in the episode is the way it slyly acknowledges that. And hell, while we’re off in the parentheticals here, I guess I can’t help myself but add that I have really, really mixed feelings about Winston Churchill the historical figure. Purely as a character in history, he’s gold: flamboyant, weird, and so good with the English language to be frequently hilarious (“If Hitler invaded hell I would make at least a favourable reference to the devil in the House of Commons” is the single funniest thing said by any of the major figures of the Second World War). He was also kind of a dickhead, was an unrepentant imperialist who caused a lot of deaths in India, and was pretty abysmal as a military leader (Churchill was directly tied to a lot of British military disasters in both of the world wars). On the other hand, he was indispensable in keeping Britain in the war in 1940, and his decision to hold a big chunk of the RAF back from the Battle of France quite possibly prevented a German invasion of the UK. Anyway, yeah, he painted.

Sutherland’s portrait of Churchill. Maybe Churchill hated it because of the missing feet.

The story plays out over the course of an hour, and it really is great to watch (among many other things, John Lithgow fucking crushes the performance as Churchill). And really, all of the drama hinges on a question that was hanging over painting and portraiture throughout the 20h century: now that photography has made the capture of an exact physical likeness both possible and easy, what’s the point of painting someone’s portrait? Is it to make them appear unrealistically heroic, as Churchill argues and hopes? Or is it to use stylization and technique to capture some deeper truth about the subject, as Sutherland believes? And if artist, subject, and patron all disagree, whose opinion wins? There isn’t a right answer to this, of course; it’s just a question that haunts portraiture now.

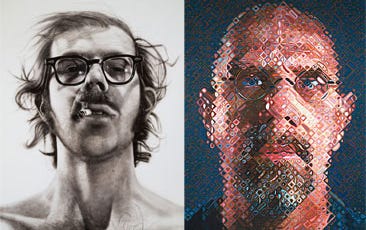

The Sutherland-Churchill imbroglio was hardly the only place where the question of what the hell the point of painted portraiture was in the age of photography. Increasingly throughout the 20th century and into the 21st, portrait painters have had to turn to stylistic and interpretive tricks to make their work relevant. Consider Chuck Close, who first tried making portraits worthwhile by working at giant scale, and then by adopting a pixelated technique.

Chuck Close’s early and late technique; note that the early sort-of-photorealistic one on the left is enormous, well over 10 feet tall. For a lot more on Close, see the Links section below.

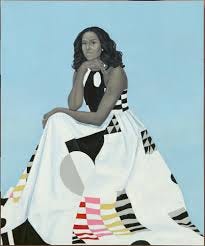

Or consider Amy Sherald, whose portrait of Michelle Obama leaned heavily on stylized touches rich with context and allusion, and briefly got the country talking about art historical interpretation when it was unveiled.

Amy Sherald’s 2018 portrait of Michelle Obama. Remember when this came out, along with Wiley’s portrait of Barack Obama, and for a week or so that’s what we were all talking about?

I guess in the end, I’m on Team Sutherland. I think painted portraits can make themselves worthwhile as something other than an exercise in raw photorealistic technique if the artist can imbue some deeper kind of truth into the picture. That’s the whole point, I think, and it’s way more important than to be flattering. If Sutherland had painted an unrealistically heroic Churchill standing in knightly robes (which is what Churchill wanted), what would that have told us about the man? Instead, the actual painting reveals something far more interesting than an idealized figure: the weathered, diminished form of someone who, even if he was a dickhead, was one of the fulcrums of history for decades. It’s much more valuable to be truly understood than to be idealized.

All good painted portraits are revealing of character. In this case, Churchill’s hatred and subsequent destruction of the painting wound up being even more revealing. So, uh, well-played, Sutherland.

Anyway, yeah. The Crown. Good quarantine watching, and there’s actually a lot more art history content beyond this, even.

Right on. Be safe.

RECOMMENDATION

Gotta be honest. Quarantine life has me short on recommendations. I recommend you get outside as much as you can safely.

A LINK

I know it’s gauche to recommend my own work, but: since I brought up Chuck Close, I want to mention that a couple of years ago, I put together a very detailed art history podcast, very much a precursor to this newsletter, where every episode would talk about some topic in art history. The show was called Artpal!, and one of my favorite episodes went in depth on Chuck Close. There’s some talk about portraiture along the same lines that I just covered, but I also go into the other thing you have to know about Close: that he’s had a lot of #MeToo allegations leveled at him, and he’s a prime case study in the problem of artists who are both canonical and deeply problematic (the absolute King of this situation is one Pablo Picasso, of course). Anyway, I think it’s a good episode (specifically, Episode 2 of Season 1) of a good podcast, and it you’re interested, you can check it out at artpalpodcast.com, or search iTunes Podcasts or whatever for “Artpal.”

CLOSING STUFF

OK, so here at the bottom, sorry for the ragged copy editing; my deal with myself was to keep this fast and loose, which is gonna mean typos. On the other hand, that also means it’ll actually come out, instead of being obsessed over.

If you have any thoughts/reactions/what have you about this, I’d love to hear about it, either by email or on Twitter. And if you know anybody who might dig this, please forward it on to them, or send ‘em the signup link! And thanks!